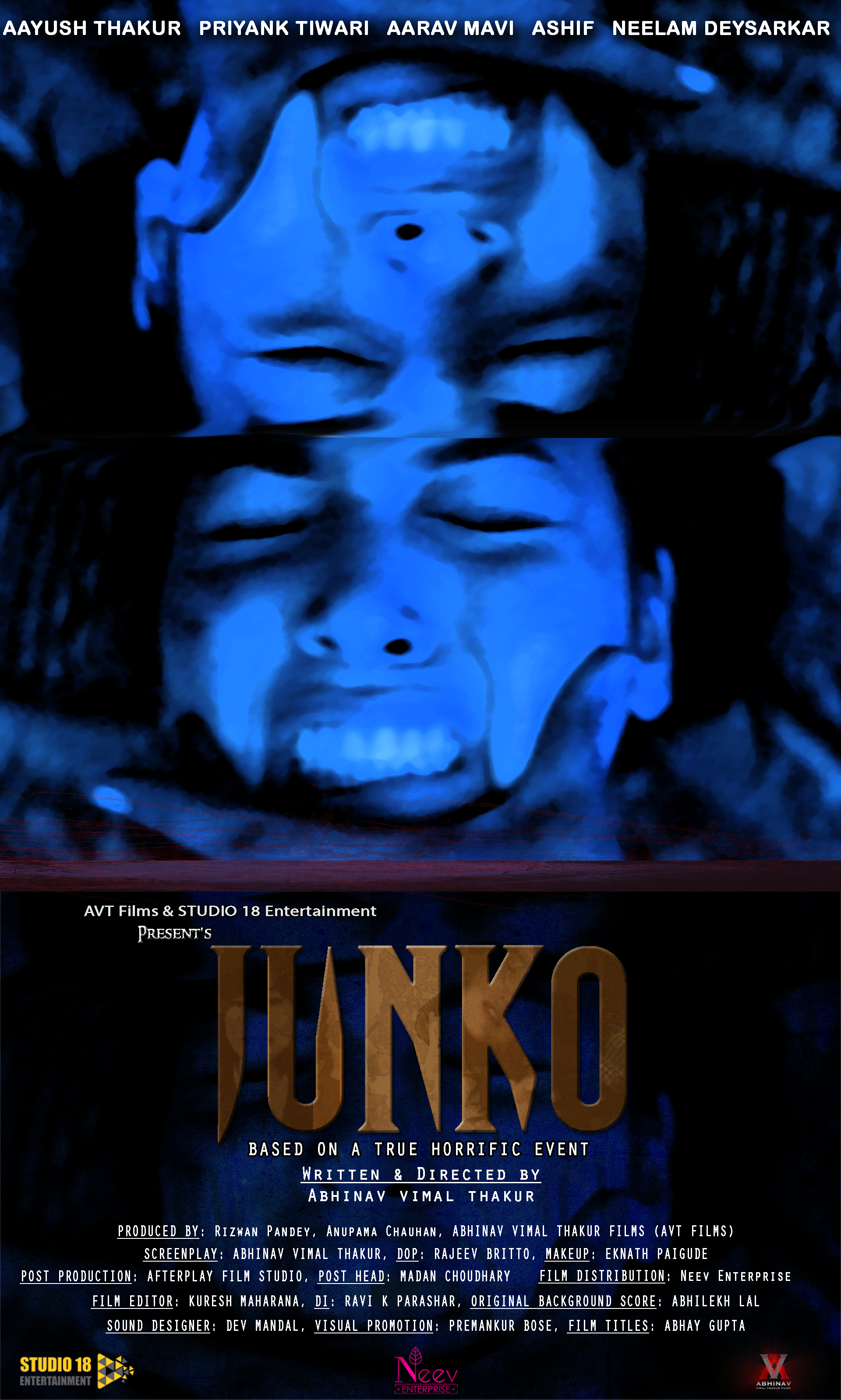

India/South Asian Independent Film Review “Junko”

WATCH THE TRAILER HERE

WATCH THE FILM HERE

First, the Recap:

When we wish to believe there is good within us all, an inherent nature contained in the soul that is born with well-intentioned notions of how we might treat our fellow human beings, it is at this time, so often it seems, that we hear or witness the capacity for truly evil deeds that can manifest from those whose conscious and sense of morality seems utterly, terrifyingly absent. The year is 1988, and it is like any other November day in the life of a young woman named Junko (Neelam Deysarkar) as she walks home via the normal route she is accustomed to. However, unbeknownst to her at this time, her existence is about to be interrupted in some of the worst imaginable ways.

Abruptly intercepted by four young men (Aayush Thakur, Aarav Mavi, Aasif Eqbal, and Priyank Tiwari), what began as a normal day quickly turns into the start of an ongoing nightmare lasting forty-four days, bound hand and foot, lying on a worn mattress in an abandoned high-rise apartment, being physically assaulted constantly by four broken, mentally disturbed men who take sick pleasure in every moment they spend inflicting the massive damage they do. Desperately clinging to life, Junko makes attempts to resist that are summarily shut down, while only inviting further abuse at the hands of her captors. Even as the men take few “breaks” outside the den of torture they’ve made, it is their non-existent ideas of mercy or remorse that seal Junko’s fate.

Next, my Mind:

A brutally realistic, unflinchingly harsh, highly disturbing, and deeply provocative, in-your-face, blunt force punch-in-the-gut viewing experience paired with well-executed, necessary, and potent intentionality is what’s behind this newest indie feature film effort from writer/director/co-producer Abhinav Thakur, based on the actual events that occurred in the all-too-short life of Japanese high-schooler Junko Furuta in late November 1988 through early January 1989. It can be seen as a risky move to be so overtly candid in the portrayal of one girl’s horrific maltreatment at the hands of the four men depicted, and this reviewer did find it hard not to be fidgeting in his seat a large portion of the time due to the graphic-enough nature of said events visualized here, yet it’s all, admittedly, a needed amount of content to illustrate the narrative’s concepts about not just the absolute cruelty and wincingly tangible pain Junko suffered, but also the absolute, merciless mentalities of these men who found joy in what they were perpetrating, even as we see the evidence of factors that have most certainly contributed to their twisted state of being.

This, of course, is by NO means explored to justify their actions, but rather quite the opposite in that it’s an actuality these types of individuals do inhabit our society and, if anything, should at minimum act as a seriously applicable warning to us to be about better ensuring that they might be found out before having the opportunity to initiate such immoral acts or at least face far better justice upon being apprehended. That latter idea is driven strongly home by actual documented facts about what Junko endured and the subsequent injustice of how truly little the men responsible paid for their actions appearing on the screen post-film, and it very much turns the stomach and induces a stir of anger when reading it. Let’s face it, getting “trapped” inside the warped mind of a group of rapists and murderers isn’t exactly uplifting, and the film’s overall execution greatly reminded me of a similar exposé of this general subject matter as portrayed in director Deepa Mehta’s 2016 film “Anatomy of Violence“, which also had a true account as its foundation.

Visually, the film hurtles the viewer into this tormented world unapologetically, especially during all the sequences in the apartment, gritty and dark, which only adds to the overall sense of discomfort you will feel while taking the story in. The events are transported to India in lieu of Japan, but this does nothing to lessen the impact of what’s shown. It’s a reality molded by strangely disconcerting strobe-lighting, images of domination posted on the apartment’s wall, cocaine-fueled actions on the part of one of Junko’s attackers, and simply heartless, inhumane, relentless savagery that leaves one totally aghast at it being another example of what humans have the capability to do to one another, much less that this actually occurred, which both causes disgust and heartrending sadness at the same time. Even when the men aren’t in the apartment, but rather just appearing to be “going about business as usual” in the city, it still showcases their detachment from any perception of virtue or integrity, which only makes the viewer even more spiteful towards them, yet, dare I say, somehow morbidly sorry for them for being so unequivocally lost as well.

From the acting standpoint, there must first be some high praise given to the four actors portraying the men–Thakur, Mavi, Eqbal, and Tiwari–collectively and individually, in that having to so fiercely, lucidly, and, frankly, sanely portray these types of individuals had to be a hugely taxing endeavor, mentally I would think for sure. The foursome just radiate the demented demeanors of their characters with a totally believable and well-enacted darkness it’s scary to see, and again, brings me to the fact that they must have had to relax, decompress, and watch Disney films between takes to regain a semblance of who they really are, one would think anyway. The four deranged men are all so calm and collected then prone to sudden and abhorrent violence towards Junko, laughing, joking, and getting ill-gained pleasure out of the pain they dole out, only sometimes choosing to “ease up” and play on their cell phones, smoke, do lines of cocaine, or just stare at their helpless, battered victim with an unbalanced look of curiosity, not seeing a human being, but rather a plaything. It’s a visceral, disquieting, yet amazing set of performances the four provide, done with such a admirable level of credibility, which is commendable given what’s being presented.

Then far equal praise must be leveled to Deysarkar as Junko, a young girl who never remotely, in any way, deserved to encounter the men that would become her doom and consign her to a concrete drum as a final resting place, only after having her endure absolute pain, humiliation, beatings, and other indecencies that are only mildly shown (making this even more unsettling given what IS chronicled) relative to what is documented at the end of the film. Throughout the story, Deysarkar so acutely and heartbreakingly portrays every ounce of fear, helplessness, hopelessness, and gut-churning agony the character is exposed to at the hands of her captors, making us as the viewer cringe and flinch in a state of abject uneasiness, making it so often hard to remain with eyes on the screen as her suffering is so hard to take in. But it’s this needed sense of authenticity and realism that makes Deysarkar’s performance so effective, formidable, and convincing, forcing the film’s greater themes home with the power of a hammer to a nail. It’s a testament to things that so urgently need to change, be confronted, and be prevented, with Deysarkar’s performance commanding such reminders, even if by necessary, ugly truths.

In total, “Junko” exemplifies the resolute, unshrinking, unwavering persuasiveness of the independent film community and its willingness to put uncomfortable truth in front of us, purposefully and with needed intent, in hopes to make societal impact, promote better awareness, and ideally to help initiate change where needed in order that we might all live in a more safe, sane, and decent world together.

As always, this is all for your consideration and comment. Until next time, thank you for reading!